“Their Fight Is Our Fight!”

The US Committee to Aid the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, 1965-1975

Memories of the struggle against the US war in Vietnam have been close to the surface for many people recently, for obvious reasons. In early June, Al Jazeera published a piece by journalist Jim Laurie comparing the media’s treatment of the encampments on US campuses to reporting on the antiwar movement in the late ‘60s. He recalls reporting on the October 1967 march on the Pentagon as a young reporter, where among the masses of demonstrators who just wanted to end the war were some who “seemed to be rooting for the Vietnamese communists to win,” prominent among them a 29-year-old activist named Walter Teague, who carried the flag of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Laurie calls it the “Viet Cong'' flag). Laurie mentions that Norman Mailer profiled Teague in his Armies of the Night. Mailer met Teague in jail after being arrested at the march, and characterizes him as an impressive, serious professional revolutionary, but one given to excessive certainty. Laurie writes that the actions of Teague and others like him who showed support for the Vietnamese revolutionaries “gave the administrations of President Lyndon B Johnson and Richard Nixon an excuse to attack the protesters…to claim all demonstrators were communist sympathisers who wanted the enemy to win.” For those of us more inclined to sympathize with the anti-imperialist wing of the ‘60s antiwar movement, a remarkable history lies behind the image of the young man at the Pentagon with the flag of the ‘enemy.’

Walter Teague was born in the late 1930s in a bourgeois family, grandson of a prominent industrial designer, but a troubled relationship with his father meant he couldn’t afford higher education. In postwar America, this meant military service. The US Air Force sent Teague to Okinawa, where he realized, as he recalled late in life, “that the United States was an empire and it was lying through its teeth to everybody.” When he returned stateside, this realization brought him into the civil rights movement and the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. The latter exposed him to the ideas of the radical left, which he accepted without joining any existing organization. When opposition to the US war in Vietnam coalesced into a mass movement in the spring of 1965, Teague was frustrated by the way the dominant forces in the movement refused to seriously challenge the administration’s rationale for the war by defending the Vietnamese struggle for independence, whether because they rejected this in principle (the liberals and pacifists) or because they felt this would alienate the public (the CPUSA and SWP). Evidently feeling that if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself, Teague and some comrades in New York City started an organization that would represent and defend the standpoint of the Vietnamese revolutionaries to the American public and the antiwar movement, calling it the US Committee to Aid the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. Early CANLF material explained: “The U.S. Committee to Aid the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam supports the aims of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam for ‘Independence, Democracy, Peace, and Neutrality.’ We support the right of the people of Vietnam for self-determination–without the presence of U.S. Troops! We wish to make the American public aware of the just and moral aims of the Vietnamese people in their resistance to the efforts of the U.S. government to ‘pacify’ their country.”

To fulfill its purposes of explaining the positions of the Vietnamese revolutionaries and of strengthening the antiwar movement by showing Americans that the Vietnamese were not their enemy, CANLF engaged in a wide range of work. They raised money and medical supplies and collected and distributed an enormous amount of literature and film from Vietnam (this clip provides a fascinating look at CANLF’s office space as of 1969, the literature and films they distributed, as well as several minutes of a wartime film from socialist Vietnam). They dispatched educational speakers to meetings of other organizations, set up literature tables, and became a consistent presence at antiwar demonstrations in New York City and national mobilizations in Washington, D.C. In its early activity, the Committee sometimes used the thirteen-star flag of the Continental Army and other American revolutionary iconography alongside that of the NLF, attempting to draw a parallel between the American struggle for independence and that of the Vietnamese.

The Committee also staked out a clear position in the movement’s internal debates. At the November 1965 convention of the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the earliest of the long series of national antiwar coalitions, they stated this position in stark terms: “We strongly believe that support of the aims and ideals of the NLF-SV is both politically and logically necessary if opposition to the war is to be more than a loud whimper. Any individual or group opposing the goals of the NLF-SV is directly supporting the goals of the Johnson administration and its Saigon puppets: that is, to crush the revolution in Vietnam and maintain an American Sphere of Influence at any price in lives and destruction. There is no middle way! We must have the courage to follow our reasoning to its logical conclusions: in the case of Vietnam, this means support of the only viable political coalition, the National Liberation Front.” A ‘Statement of Policy’ released in the same month argued in similar terms: “Those in this country who are for ‘Peace’ but refuse to concern themselves with who the people ‘on the other side’ are, what is motivating them to fight, and why the U.S. is really involved in Vietnam, are by default supporting the policies and efforts of the U.S. government to stop the liberation struggles of people everywhere.”

These views earned the Committee many enemies in the leadership of the antiwar movement (not to mention the hostile attention of the state: Teague was summoned by HUAC and Committee members were frequently arrested, but strong defense campaigns seem to have kept them out of prison most of the time). But as the movement grew and radicalized, a growing current of young activists would come over to the positions of Teague and his comrades. CANLF, for its part, never shied away from a fight. In the spring of 1967 the Committee joined with other radical left groups in forming a ‘Revolutionary Contingent’ for the Spring Mobilization demonstration in New York, founded on a critique of the “Official Movement'' whose failure to side with the revolutionary forces rendered it “the government’s ‘Loyal Opposition’' who had used “the ambiguous slogan of ‘Stop the War Now!’” to obscure “the most fundamental character of the war in Vietnam..” This struggle with the dominant forces in the movement continued around the October 1967 march on the Pentagon (where Teague made such an impression on Norman Mailer and the young Jim Laurie). CANLF helped organize a “Vietnamese Contingent” including both Americans and Vietnamese expatriates who supported the revolutionary forces. In their fall newsletter, the Committee described how they were “successful in pressuring the ‘leadership’ into allocating an entire major section of the rally-march” to these forces, a victory over “the ‘Negotiationist’ position of the conservative leadership.’” They also won space for a Vietnamese-American activist named Nguyen Van Luy to address the march with a speech in support of the Vietnamese resistance, although the organizers cut him off a few minutes in, supposedly for lack of time (decades later, Teague still considered this “[a]n insult to a fine man and the Vietnamese-American peace movement”). Finally, the Vietnamese Contingent along with SDS managed to precipitate the famous ‘storming’ of the Pentagon’s lawn, which according to CANLF, “the ‘leadership’ was trying to stall out of existence!” The Committee felt the Pentagon was a triumph for their perspective, leading to “the realization by increasing numbers of peace activists that our real enemy lies in Washington–and that the people of Hanoi, Haiphong, Long Binh and Dak To are our friends–that they are, in fact, our allies in our hopes, aspirations, and struggles for a life of dignity and happiness free from oppression–for our own self-determination in America.”

The march on the Pentagon combined a number of elements that would remain central to CANLF’s interventions in the antiwar movement: besides the obvious one of explicit support for the Vietnamese revolutionary forces, these include efforts to build coalitions of radical groups and the use of militant–or as they often called them, “mobile”–tactics in the streets. All these elements would also be on full display in the streets of New York City in the spring of 1968. CANLF and other groups who shared a critique of the “CP-SWP-Pacifist Coalition” leading the movement were already planning an “anti-imperialist feeder march” to a rally being held by the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee on April 27, 1968, when they learned that the Parade Committee had invited New York’s Mayor John Lindsay to speak. Lindsay was one of the most prominent liberal politicians in America, but his administration had just passed a racist, repressive ‘Emergency Law,’ and his invitation led SNCC to withdraw from the rally, arguing that Lindsay and his liberal ilk were only against the war because the US was losing, and stating that “[w]ith this rally the white antiwar movement shows its complete irrelevance to Black people.” CANLF and its allies saw the need and opportunity to challenge what they saw as an effort by the forces of liberalism to “take over the leadership of our movement completely and turn it into a loyal oppositionist movement which will never break with the system and therefore will give in to the ruling class at all crucial points.” (It’s worth noting that one point these radicals made against the mainstream leaders of the movement was their refusal to “have the movement take positions on imperialist involvement in other parts of the world…such as the U.S.-Israeli aggression against the Arab people.”). They organized an alternative demonstration which, despite being attacked by the police, was able to reach the mass rally and lead some participants away towards student-occupied Columbia University.

On May 18, the same groups, now constituted as the ‘Coalition for An Anti-Imperialist Movement’ or Co-Aim, held a second militant demonstration in the same area. Volunteer Jane Jaffe gloated in the CANLF newsletter that “even the New York Times had to admit that we ‘fooled’ and ‘outwitted’ the police,” and that they had “‘liberated’ the Lower East Side streets for a few hours.” A Co-Aim leaflet on the two demonstrations argued: “under these circumstances, the liberal imperialist rulers of New York City had to decide whether to use a degree of force to stop the march that would show far too much of the iron fist beneath the silk glove, or let us go. This time, rather than reveal the true nature of their system, they backed down.”

Co-Aim, which appears to have lasted for roughly a year, brought together a range of radical groups in New York City, from well-known organizations like Workers World Party/Youth Against War and Fascism to the obscure but intriguing ‘Blacks Against Negative Dying.’ In the heat of the worldwide upheavals of 1968, the coalition sponsored demonstrations supporting student revolt in France and opposing repression in Mexico, a recurring workshop on “tactical street action,” and continued antiwar action and resistance to local police repression. As the New Left turned increasingly to revolutionary, anti-imperialist politics at the end of the ‘60s, CANLF felt themselves swimming with the stream and became increasingly forthright about the need not just for support for the Vietnamese revolution, but for revolution in the US. After explaining the reasons for the group’s formation, a leaflet from 1968 went on:

“Today, 3 years later, we are proud to be part of a growing anti-imperialist movement within the U.S. itself. The increasing numbers of Americans who realize that they must commit themselves to a revolutionary change within their own country, owe a profound debt to the heroic Vietnamese. The example of imperialism in Vietnam has made it possible for Americans to understand U.S. exploitation in Latin America, Asia, Africa and elsewhere. The understanding and compassion that we have gained for the liberation struggle of the Vietnamese has made it easier for us to understand and side with the growing struggle of the oppressed peoples within the U.S.

Those of us who support the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam do so not just because their fight is just, but because THEIR FIGHT IS OUR FIGHT!”

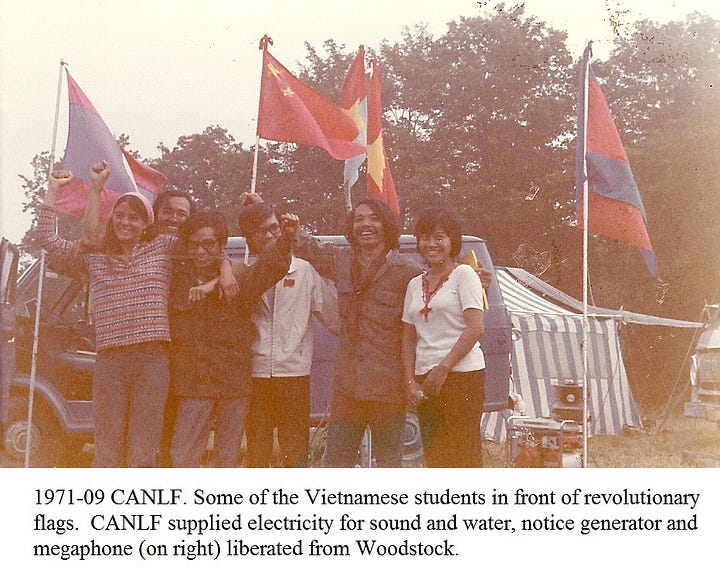

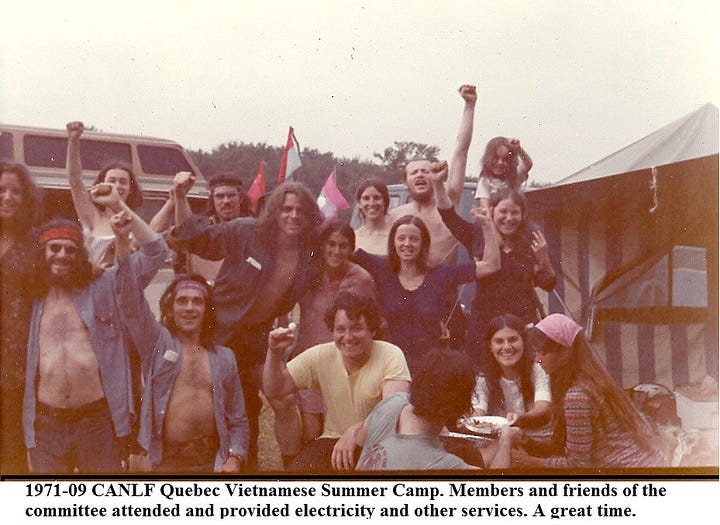

Committee activists’ sense that the fight of the Vietnamese was their fight was strengthened by direct contact with Vietnamese revolutionaries. The Committee corresponded with the NLF from its beginnings, and from the later 1960s CANLF delegates met with their representatives at several international conferences. In the summer of 1971, Committee members played an important role in an extraordinary initiative intended to build relationships between the US movement and the Vietnamese. On August 12, the Committee sent out a letter informing their supporters of a plan by the Montreal-based Association of Vietnamese Patriots in Canada, an organization mainly made up of students from ‘South’ Vietnam who supported the revolution, to host a ‘summer camp’ in southern Quebec for American antiwar activists that September. Tran Tu described the camp’s purposes on behalf of the Association in another letter a week later:

“1. To build closer contact between Vietnamese living in Canada and U.S. movement people.

2. To exchange political and cultural viewpoints.

3. To help bring the anti-war movement together and to build better understanding among movement people.

4. To further our joint efforts to bring the Viet Nam war to an end.”

Besides the camp’s formal program, Tu expressed the hope that “In coming together to camp, talk, and dance we can break down the barriers between ourselves and our two peoples and share our revolutionary love.”

To these ends, CANLF encouraged US organizations to send a member who “has been doing daily work against the war or for your community, someone who doesn’t usually get the chance to go to conventions, etc. or meet with our Vietnamese friends.” The camp’s proposed schedule included six days of workshops on the development of the Vietnamese revolutionary forces and the US antiwar movement, Vietnamese and American culture, films, and time to socialize. A note on the schedule warned that “The times and circumstances demand that we all observe the discipline of not endangering our Vietnamese and Quebecois friends and ourselves by bringing drugs or anything illegal (except our love and ideas) to the camp.” In its December 1971 newsletter, CANLF wrote that the camp had been an “educational and revealing” experience for them and the approximately one hundred and fifty US activists who attended, allowing them to learn “much about the Vietnamese people and their culture–also about our movement, its strong and weak points.” A November 1972 newsletter indicates that the camp was repeated the following year. Even from the limited account available in the CANLF documents archived by Walter Teague, it’s clear that the camp represented a truly remarkable reflection of the commitment of anti-imperialists in the antiwar movement to reach out to ‘the other side.’

The withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973 led to the end of the mass antiwar movement in the US, but for anti-imperialist groups like CANLF the struggle continued as long as the US air war and aid to Indochina’s reactionary regimes persisted. The nature of the Committee’s activity did not change, but its focus now broadened to include the revolutionary forces in Laos and Cambodia and the socialist state in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. To reflect this shift, in its June 1973 newsletter CANLF announced that it was changing its name to the Indochina Solidarity Committee. While hailing the agreements signed in Vietnam and Laos as victories for the revolution, the Committee warned that “the U.S. government will never give up voluntarily, nor admit its defeat in Indochina: new tactics are planned and are being put into effect in an effort to find the formula that will crush the Indochinese revolution and the example it gives to the rest of the world.” Lamenting the dissipation of the mass antiwar movement (“too many Americans either believe the war is over, don’t know what to do about it or just don’t care”) the ISC argued that those “radicalized by the heroic struggle of the Indochinese peoples” were obligated to continue, “rebuilding the anti-war movement into a continuing, anti-imperialist movement.”

Besides the ongoing struggles in Southeast Asia, the Indochina Solidarity Committee’s life would be shaped by wider developments on the US left in the 1970s. As the intensity and scale of mass mobilization declined, many of the most radical and committed activists turned to the emerging Marxist-Leninist organizations of the New Communist movement. The first such group to gain a national profile was the Revolutionary Union, which by around 1974 had attracted the support of the majority of the ISC’s core members. Teague and another member, Martha Chamberlain, remained aloof. The RU supporters in the Committee adopted the same sectarian, manipulative approach that made the organization notorious in the wider movement. To take one example, while the nature of the Committee’s work had always meant their resources were available to anyone who wanted them, the RU-affiliated members began controlling access according to RU politics, denying their use to “feminist groups…groups associated in any way with Trotskyist or Prairie Fire politics, or supporters of the Soviet Union.” The RU’s dogmatic adherence to China’s political line also increasingly placed the Committee’s messaging at odds with the views of the Vietnamese themselves. Relations within the ISC began to break down, and in the aftermath of the final revolutionary victory in Vietnam in spring 1975, the non-RU members proposed the group be closed down. This precipitated a split, whose convoluted details–including a physical confrontation and a long dispute over the Committee’s materials–can be followed here.

In the midst of this split, Teague and Chamberlain sent a letter to the representatives of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam in Paris attempting to explain the situation. The self-descriptions they included in this letter give a touching window into the ways the anti-imperialist politics of the era transformed those who took it up. Chamberlain grew up in the rural Midwest and became involved in politics at the age of eighteen as a campaign volunteer for Eugene McCarthy, “because of moral outrage at the war and killing.” Within a few years she had adopted an anti-imperialist perspective and joined CANLF in 1971. She spent the following years immersed in Indochina solidarity, and also travelled to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade in 1973.

It is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the self-description given by the Committee’s founder Walter Teague that best sums up its historical significance:

“My primary motivations have been not only deep admiration and identification with your struggle, but also a clear understanding of how opposition to the U.S. war in Indochina and building support for liberation struggles (your’s in particular) have led to a revitalization and advancement of our own progressive and revolutionary movement here in the U.S. I am old enough to have grown up in an America almost devoid of political or class consciousness following the setbacks for the progressive forces in the late 1940’s and 50’s. The U.S. in the 60’s and 70’s is a drastically different place and the momentum and depth of the political change are irreversible.

In a word, at a time when no clear single revolutionary force existed in the U.S., it has been my way of joining the worldwide revolution.”